Modal Examples

01_getting_started

This is a Quarto book with notes on running Modal examples, which is a GitHub repo filled with use cases for running Modal.

This book is meant as a personal reference and not an official guide on Modal.

Modal lets you run code in the cloud without having to think about infrastructure.

Features

- Run any code remotely within seconds.

- Define container environments in code (or use one of our pre-built backends).

- Scale out horizontally to thousands of containers.

- Attach GPUs with a single line of code.

- Serve your functions as web endpoints.

- Deploy and monitor persistent scheduled jobs.

- Use powerful primitives like distributed dictionaries and queues.

The nicest thing about all of this is that you don’t have to set up any infrastructure. Just:

- Create an account at modal.com

- Run

pip install modalto install the modal Python package - Run

modal setupto authenticate (if this doesn’t work, trypython -m modal setup)

…and you can start running jobs right away.

Modal is currently Python-only, but it may support other languages in the future.

How does it work?

Modal takes your code, puts it in a container, and executes it in the cloud.

Where does it run? Modal runs it in its own cloud environment.

The benefit is that we solve all the hard infrastructure problems for you, so you don’t have to do anything. You don’t need to mess with Kubernetes, Docker or even an AWS account.

All credit should be given to the Modal team for a wonderful tool and examples repo.

So after you’ve created a Modal account, let’s first to setup your environment locally.

0.1 Clone repo

git clone https://github.com/modal-labs/modal-examples.git0.2 Modal setup

$ modal setup

The web browser should have opened for you to authenticate and get an API token.

If it didn't, please copy this URL into your web browser manually:

https://modal.com/token-flow/tf-xxxxxxxxxxx

Web authentication finished successfully!

Token is connected to the charlotte-llm workspace.

Verifying token against https://api.modal.com

Token verified successfully!

Token written to /Users/ryan/.modal.toml in profile charlotte-llm.1 hello_world.py

Now we’ll start with this file:

hello_world.py

import sys

import modal

app = modal.App("example-hello-world")

@app.function()

def f(i):

if i % 2 == 0:

print("hello", i)

else:

print("world", i, file=sys.stderr)

return i * i

@app.local_entrypoint()

def main():

# run the function locally

print(f.local(1000))

# run the function remotely on Modal

print(f.remote(1000))

# run the function in parallel and remotely on Modal

total = 0

for ret in f.map(range(20)):

total += ret

print(total)1.1 Running locally, remotely, and in parallel

Let’s focus in the main() part of the script.

It calls our function, f, in three different ways:

- As a regular

localcall on your computer, withf.local - As a

remotecall that runs in the cloud, withf.remote - By

mapping many copies offin the cloud over many inputs, withf.map

We can execute this script by running modal run hello_world.py:

$ cd 01_getting_started

$ modal run hello_world.py

✓ Initialized. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxx

✓ Created objects.

├── 🔨 Created mount /modal-examples/01_getting_started/hello_world.py

└── 🔨 Created function f.

hello 1000

1000000

1000000

hello 1000

hello 0

world 1

hello 2

world 3

hello 4

world 5

hello 6

world 7

hello 8

world 9

hello 10

world 11

hello 12

world 13

hello 14

world 15

hello 16

world 17

hello 18

world 19

2470

Stopping app - local entrypoint completed.

✓ App completed. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxx1.1.1 What just happened?

When we called .remote on f, the function was executed in the cloud, on Modal’s infrastructure, not locally on our computer.

In short, we took the function f, put it inside a container, sent it the inputs, and streamed back the logs and outputs.

1.1.2 But why does this matter?

Try doing one of these things next to start seeing the full power of Modal!

1.1.3 Change the code

I’ll change the print to “spam” and “eggs”:

hello_world_spam.py

import sys

import modal

app = modal.App("example-hello-world")

@app.function()

def f(i):

if i % 2 == 0:

print("spam", i)

else:

print("eggs", i, file=sys.stderr)

return i * i

@app.local_entrypoint()

def main():

# run the function locally

print(f.local(1000))

# run the function remotely on Modal

print(f.remote(1000))

# run the function in parallel and remotely on Modal

total = 0

for ret in f.map(range(20)):

total += ret

print(total)Then run:

$ modal run hello_world_spam.py

✓ Initialized. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxx

✓ Created objects.

├── 🔨 Created mount /modal-examples/01_getting_started/hello_world_spam.py

└── 🔨 Created function f.

spam 1000

1000000

spam 1000

1000000

spam 0

eggs 1

spam 2

eggs 3

spam 4

eggs 5

spam 6

eggs 7

spam 8

eggs 9

spam 10

eggs 11

spam 12

eggs 13

spam 14

eggs 15

spam 16

eggs 17

spam 18

eggs 19

2470

Stopping app - local entrypoint completed.

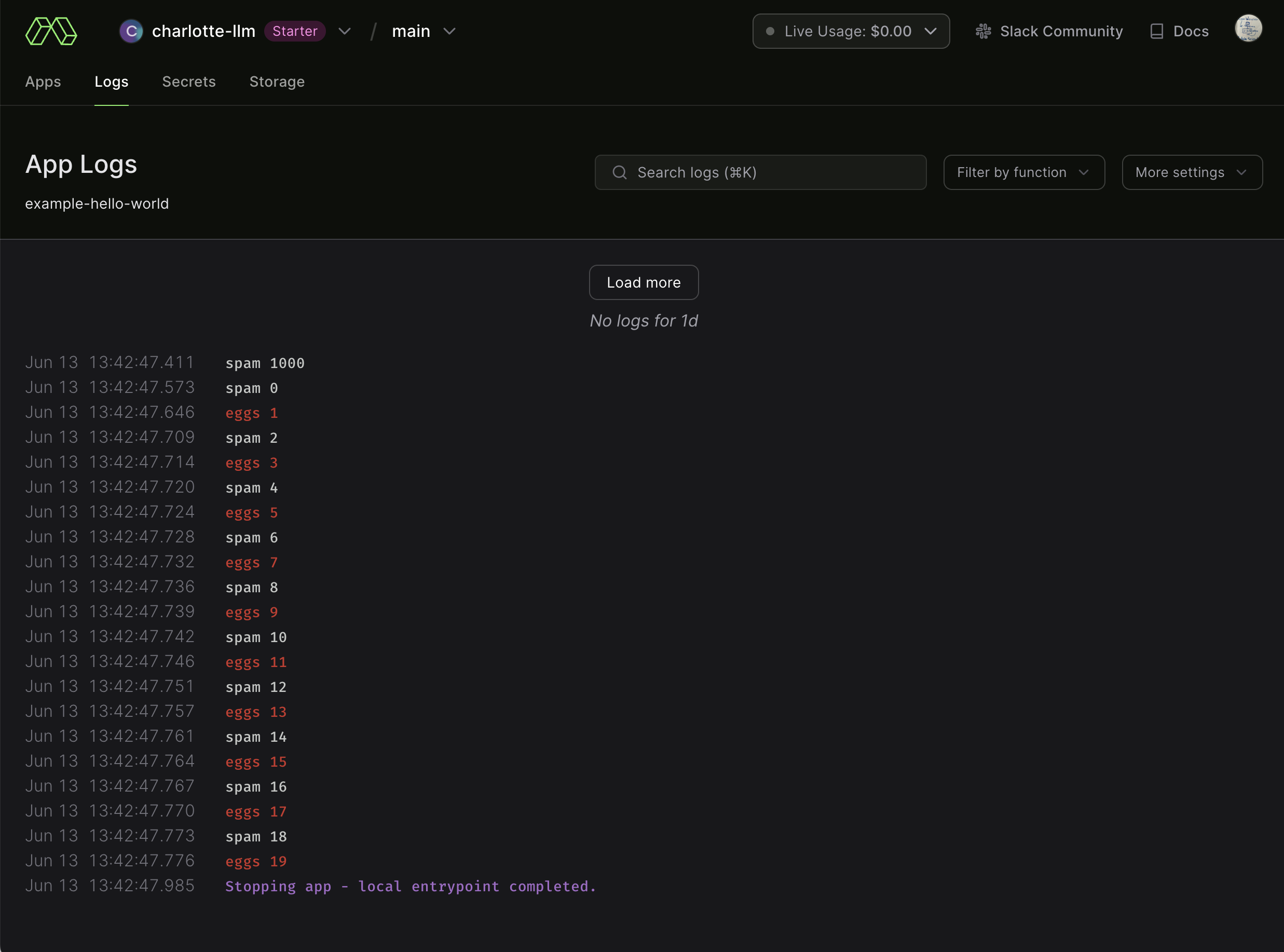

✓ App completed. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxxI can view the output via browser:

This example is obviously very simple, but there are many other things you can do with modal like:

- Running language model inference or fine-tuning

- Manipulating audio or images

- Collecting financial data to backtest a trading algorithm.

2 get_started.py

Now let’s look at the next file:

get_started.py

import modal

app = modal.App("example-get-started")

@app.function()

def square(x):

print("This code is running on a remote worker!")

return x**2

@app.local_entrypoint()

def main():

print("the square is", square.remote(42))2.1 Decorators

Notice the two different app decorators: @app.function() and @app.local_entrypoint().

local_entrypoint:

> def local_entrypoint(

self, _warn_parentheses_missing=None, *, name: Optional[str] = None

) -> Callable[[Callable[..., Any]], None]:Decorate a function to be used as a CLI entrypoint for a Modal App.

These functions can be used to define code that runs locally to set up the app, and act as an entrypoint to start Modal functions from. Note that regular Modal functions can also be used as CLI entrypoints, but unlike local_entrypoint, those functions are executed remotely directly.

@app.local_entrypoint()

def main():

some_modal_function.remote()You can call the function using modal run directly from the CLI:

modal run app_module.pyNote that an explicit app.run() is not needed, as an app is automatically created for you.

We can run:

$ modal run get_started.py

✓ Initialized. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxx

✓ Created objects.

├── 🔨 Created mount /modal-examples/01_getting_started/get_started.py

└── 🔨 Created function square.

the square is 1764

This code is running on a remote worker!

Stopping app - local entrypoint completed.

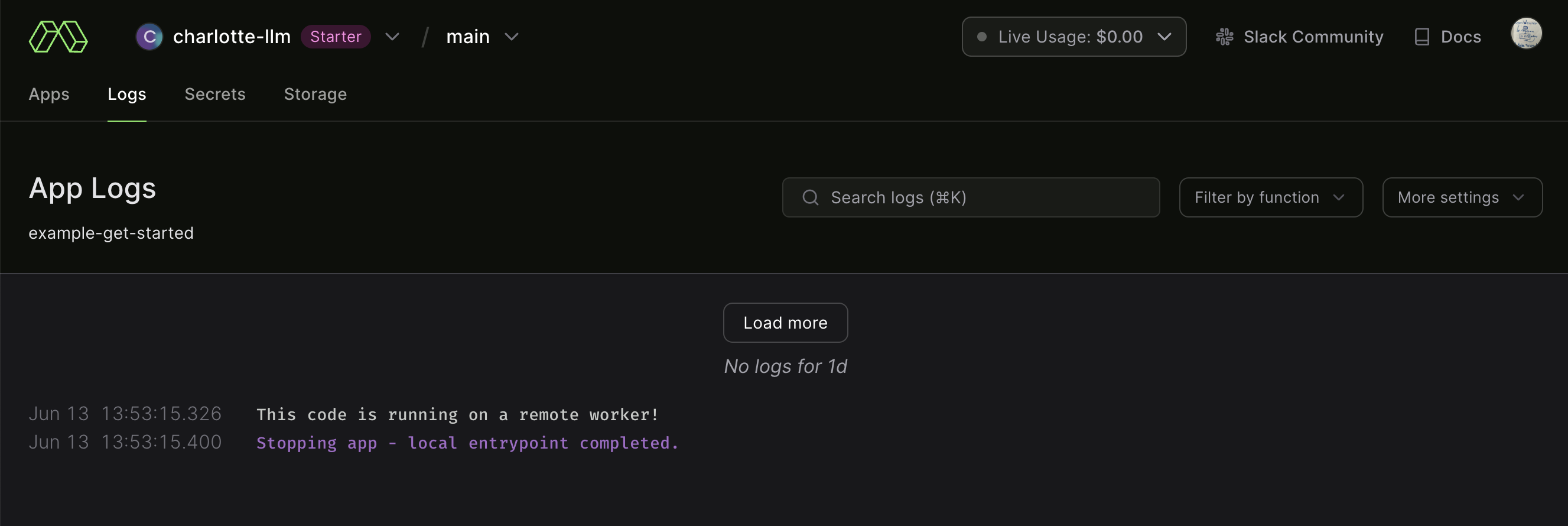

✓ App completed. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxxNow I wonder what happens if I create a similar new file:

get_started_local.py

import modal

app = modal.App("example-get-started-local")

@app.function()

def square(x):

print("This code is running on a local worker!")

return x**2

@app.local_entrypoint()

def main():

print("the square is", square.local(42))And then run:

$ modal run get_started_local.py

✓ Initialized. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxxx

✓ Created objects.

├── 🔨 Created mount /modal-examples/01_getting_started/get_started_local.py

└── 🔨 Created function square.

This code is running on a local worker!

the square is 1764

Stopping app - local entrypoint completed.

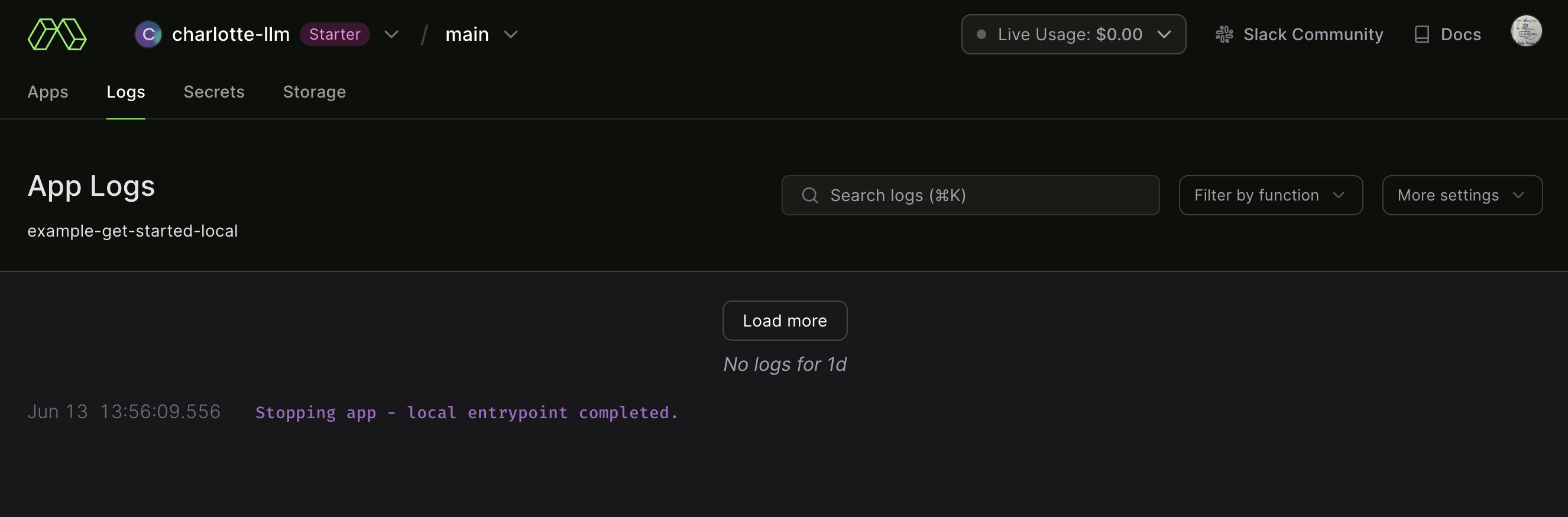

✓ App completed. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxxxVery similar. What happens when we look at the logs:

3 generators.py

We can also glance at how generators vary for remote vs local with:

generators.py

import modal

app = modal.App("example-generators")

@app.function()

def f(i):

for j in range(i):

yield j

@app.local_entrypoint()

def main():

for r in f.remote_gen(10):

print(r)Importing Modal

The script starts by importing the modal module.

Defining the Modal App

The next line creates a Modal application instance, named “example-generators”, using the modal.App constructor.

Defining a Generator Function

The f function is defined as a generator function using the @app.function() decorator. This decorator registers the function with the Modal app, making it available for remote execution.

The f function takes an integer i as input and yields a sequence of numbers from 0 to i-1 using a for loop. The yield statement is used to produce each number in the sequence, rather than computing the entire sequence at once.

Defining a Local Entry Point

The main function is defined as a local entry point using the @app.local_entrypoint() decorator. This decorator marks the function as the entry point for the Modal app, which means it will be executed when the app is run locally.

Remote Execution and Printing

In the main function, the f.remote_gen(10) expression is used to execute the f function remotely with an input of 10. The remote_gen method returns a generator that produces the output of the remote execution.

The for loop iterates over the generator, printing each number in the sequence produced by the remote execution of f.

How it Works

When the script is run, the Modal app is created, and the main function is executed locally. The main function executes the f function remotely with an input of 10, which produces a sequence of numbers from 0 to 9. The generator returned by remote_gen is iterated over, printing each number in the sequence.

Note that the f function is executed remotely, which means it can be executed on a different machine or in a different process, depending on the Modal configuration. This allows for distributed execution and scaling of the application.

Then if we run:

$ modal run generators.py

✓ Initialized. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxxx

✓ Created objects.

├── 🔨 Created mount /modal-examples/01_getting_started/generators.py

└── 🔨 Created function f.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Stopping app - local entrypoint completed.

✓ App completed. View run at https://modal.com/charlotte-llm/main/apps/ap-xxxxxxxxxx